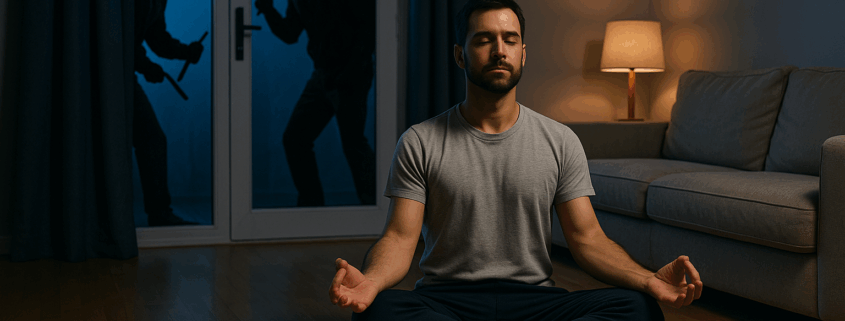

What a Homeowner Must Do Before Using Force in Canada

Unlike the U.S. castle doctrine, Canadian law does not presume that a homeowner can automatically use force when an intruder enters. Instead, the Criminal Code (ss. 34–35) requires that several conditions be met.

1. Assess the Situation

The homeowner must first believe, on reasonable grounds, that they or another person are being threatened with force, or that property is at risk of being damaged or stolen. Mere trespass, without threat, does not usually justify force.

2. Attempt to Avoid Violence (If Possible)

While Canada does not impose a strict “duty to retreat,” courts expect homeowners to consider non-violent options first:

- Calling police or security

- Issuing a verbal warning (e.g., “Get out of my house”)

- Securing themselves and others in a safe area if escape is possible

If a homeowner rushes to violence without trying other measures, the use of force may later be found unreasonable.

3. Use Only the Force Necessary

If force becomes unavoidable, the law requires it to be reasonable and proportionate to the threat.

- Minimal force (like physically ejecting a trespasser) is permitted to protect property.

- Escalating to weapons or deadly force is only justified if the intruder poses an imminent threat to life or serious bodily harm.

4. Deadly Force = Last Resort

Lethal force may only be used if the homeowner reasonably believes it is the only way to stop a threat of death or grievous bodily harm. Protecting property alone (like a vehicle, electronics, or cash) never justifies deadly force under Canadian law.

Judicial Considerations

When courts evaluate a homeowner’s actions, they look at factors such as:

- Immediacy of the threat — Was the intruder armed? Advancing?

- Options available — Could the homeowner retreat or call for help?

- Proportionality — Was the force used excessive compared to the threat?

- Role of the homeowner — Did they instigate or escalate the conflict?

These checks mean Canadian law emphasizes restraint and necessity, not a blanket right to defend property at all costs.

Canadian Case Examples

Canadian courts have already faced difficult decisions in homeowner defence cases. Here are two examples that illustrate the limits of the law:

Example 1 – Homeowner Found Not Guilty

In R. v. Khill, 2021 SCC 37, a Hamilton-area homeowner was charged with second-degree murder after fatally shooting an intruder who was trying to break into his truck at night. The Supreme Court of Canada ultimately ordered a new trial but emphasized that self-defence is highly context-dependent: the jury must consider what the accused reasonably perceived at the time. While Khill was not outright acquitted at the SCC level, the case reflects how a homeowner can successfully argue they acted in defence of themselves and their property when they reasonably feared for their safety.

Example 2 – Homeowner Found Guilty

In R. v. Deegan, 2007 ONCA 81, an Ontario man shot and killed an unarmed intruder who had broken into his home. The intruder posed no immediate lethal threat, and the court found the homeowner’s response to be disproportionate. Deegan was convicted of manslaughter, showing that Canadian courts draw a firm line: force may be used to defend property, but not deadly force unless there is a clear threat to life.

Conclusion

Canadian law makes it clear: defending your home is not the same as having an automatic right to use force. Before acting, homeowners must assess the situation, consider non-violent alternatives, and ensure that any force used is both necessary and proportionate. Deadly force remains an absolute last resort, available only when life or serious safety is immediately at risk.

Cases like Khill and Deegan highlight the fine line Canadian courts draw between justifiable self-defence and criminal liability. For property owners, the lesson is simple: while your home may feel like your castle, the law requires restraint and responsibility before force can be used.

At Rabideau Law, we help homeowners, landlords, and investors understand not only their real estate rights, but also how those rights interact with broader Canadian laws. If you have questions about protecting your property and your interests, our team is here to guide you.